Here is a dialogue extract from my new novel. But, does it pass the acid test? Does it move the plot along and does it create interest? You can decide.

“Have you seen this?” he asks, pointing above to a square containing sixteen smaller ones, each carved with a number. They gather close and focus on the strange pattern.

Ted is intrigued, “I love these puzzles, but what does it mean?”

“I was never good with numbers,” adds Claudine. “I preferred Music and the Arts.”

“Oh, this is very much Art,” Michael replies. “It’s the Art of Numbers.” He points, “If you add up the numbers in the first row, what is the total?”

“33,” says Ted, without hesitating.

“Very good,” says Michael. “What about the total in each of the other rows?”

“They add up to 33 too.”

“Well done. Do you notice any other patterns?”

Suzie was first to guess, “Why, each column makes a total of 33 as well.”

“Aha, very good indeed. What about the diagonals?”

“33 for both of them. That’s amazing.”

“Bravo, but what is significant about the number 33?”

“I have it,” Claudine finally announces.

“Really?” asks Michael. “I thought you hated numbers.”

All dialogue should pass the following criteria:

- It must move the story forward. After each conversation or exchange, the reader should be one step closer to either the climax or the conclusion of your story.

- It should reveal relevant information about the character. The right dialogue will give the reader insight into how the character feels, and what motivates him or her to act.

- It must help the reader understand the relationship between the characters.

If your dialogue doesn’t accomplish all of the above, it is a waste of words.

The best dialogue is brief

It’s a slice and not the whole pizza. You don’t need to go into lengthy exchanges to reveal an important truth about the characters, their motivations, and how they view the world. Plus, dialogue that goes on for too long can start to feel like a tennis match with the reader switching back and forth between characters. Lengthy dialogue can be exhausting for the reader. Pair the dialogue down to the minimum that you need for the characters to say to each other.

Avoid small talk

In your novel, never ever waste your dialogue with small talk.

In the real world, small talk fills in the awkward silence, but in the world of your novel, the only dialogue to include is the kind that reveals something necessary about the character and/or plot. How’s the weather? doesn’t move the plot.

Don’t info dump

While you can certainly use dialogue to learn more about your characters, you shouldn’t use it to dump a whole lot of information on the reader.

It’s cringeworthy to read a dialogue exchange that starts with:

“As you know…”

If the character already knows, then why is the other character repeating it?

Be consistent

Remember to be consistent with your characters. Someone who speaks in a self-depreciating and shy demeanor won’t automatically become bold and acerbic.

When your characters speak, they should stay true to who they are. Even without character tags, the reader should be able to figure out who’s talking.

Create suspense

Use dialogue to increase the suspense between characters.

Minimize identifying tags

Minimize identifying tags

“He said, she said” gets boring after a while. And the answer isn’t to switch out those “said” tags with other words like “enthused” or “shouted”. (By the way, when it doubt, “said” wins out.)

Not only is it boring for the reader to constantly see “he said” or “said she”, it’s also disruptive. Identifiers take the reader out of the immersive world of your story and reminds them that you, the author, are relaying a story. That can be pretty jarring, and it can happen if you use identifiers too often.

Of course, you can’t not use identifiers. They’re vital for establishing who’s speaking, but can be minimized by doing the following:

- Creating a unique pattern of speech, as we discussed above.

- Using descriptive follow ups. (i.e. “That’s not what I said.” Vincent reached for the rock.)

Read it aloud

During the editing process, you should always read your manuscript aloud, but do pay special attention to your dialogue.

If the dialogue doesn’t seem to flow, or you’re tripping over your words, it’s not going to sound right to the reader.

[Read more here from the NY Book Editors. Meanwhile, how did I score?]

The one sentence pitch is the essence or heart of a book, the line that tells people about your book and makes it sound awesome.

The one sentence pitch is the essence or heart of a book, the line that tells people about your book and makes it sound awesome.

There’s one thing every writer needs to master, and that is how to leave a lasting impression on readers—how to end their story. Should it be unresolved or ambiguous; unexpected or dramatic? As writers, we have plenty of options. So, you might ask, what worked for me in my latest novel? More on this to come, suffice to say that I changed the ending a few times, more or less in keeping with my editing and having more time to review it. In the end (pun intended), I changed the ending to tie up a loose end near the beginning. I could tell you more, but that would be giving the plot away. OK, here’s a glimpse of the beginning of the final chapter:

There’s one thing every writer needs to master, and that is how to leave a lasting impression on readers—how to end their story. Should it be unresolved or ambiguous; unexpected or dramatic? As writers, we have plenty of options. So, you might ask, what worked for me in my latest novel? More on this to come, suffice to say that I changed the ending a few times, more or less in keeping with my editing and having more time to review it. In the end (pun intended), I changed the ending to tie up a loose end near the beginning. I could tell you more, but that would be giving the plot away. OK, here’s a glimpse of the beginning of the final chapter: Minimize identifying tags

Minimize identifying tags What’s in a name? Everything. A few years ago a Chinese friend of mine rang to ask if New Zealand baby names had meanings. “Of course,” I said. He next asked, “What name means mistake?”

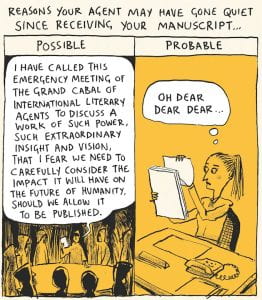

What’s in a name? Everything. A few years ago a Chinese friend of mine rang to ask if New Zealand baby names had meanings. “Of course,” I said. He next asked, “What name means mistake?” Finding the right literary agent is harder than finding a partner. When I co-authored my school textbook, the editor from Macmillan’s was perfect—professional, yet sympathetic; warm and encouraging, though not reluctant to steer us in the right direction. She knew her craft and the final product was excellent. When it comes to novels, I am no expert on literary agents because I have yet to find the right one. But, I am sure that when I do, they will be like my textbook editor and have my best interests at heart. Meanwhile, I keep working on producing the very best manuscript I can; one that is polished, error free, and compelling in terms of plot and pace. I have learned not to treat my agent query like a round of speed-dating, but to focus on the agent who has the same interests as me and the experience to navigate the best publishing deal. How long will this take? Months or years. Does it matter if the novel is able to stand the test of time?

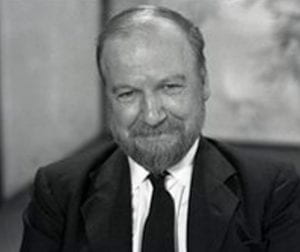

Finding the right literary agent is harder than finding a partner. When I co-authored my school textbook, the editor from Macmillan’s was perfect—professional, yet sympathetic; warm and encouraging, though not reluctant to steer us in the right direction. She knew her craft and the final product was excellent. When it comes to novels, I am no expert on literary agents because I have yet to find the right one. But, I am sure that when I do, they will be like my textbook editor and have my best interests at heart. Meanwhile, I keep working on producing the very best manuscript I can; one that is polished, error free, and compelling in terms of plot and pace. I have learned not to treat my agent query like a round of speed-dating, but to focus on the agent who has the same interests as me and the experience to navigate the best publishing deal. How long will this take? Months or years. Does it matter if the novel is able to stand the test of time? William Golding’s most famous book, Lord of the Flies, had been rejected by every publisher he sent it to – until an editor at Faber pulled his manuscript off the rejection pile.

William Golding’s most famous book, Lord of the Flies, had been rejected by every publisher he sent it to – until an editor at Faber pulled his manuscript off the rejection pile. The analogy is cutting and polishing diamonds. Cutting is crucial, and the same applies to a manuscript. In my latest script, the rough draft had an opening chapter that I cut in order to begin at a more important part of the plot. For a diamond, the final polishing of all the facets is a crucial step in determining the quality and beauty of the finished gem. This takes far more time and painstaking attention to detail. I would have to say that this process of polishing the script, editing and re-editing is taking far longer than I expected. But, I guess I am my worst critic and I am at the level of getting ruthless with each word now. Hopefully, the final product will be polished enough to pass the critic test.

The analogy is cutting and polishing diamonds. Cutting is crucial, and the same applies to a manuscript. In my latest script, the rough draft had an opening chapter that I cut in order to begin at a more important part of the plot. For a diamond, the final polishing of all the facets is a crucial step in determining the quality and beauty of the finished gem. This takes far more time and painstaking attention to detail. I would have to say that this process of polishing the script, editing and re-editing is taking far longer than I expected. But, I guess I am my worst critic and I am at the level of getting ruthless with each word now. Hopefully, the final product will be polished enough to pass the critic test.