This intriguing article floated into my reading space and collided with another one detailing the main reason for manuscript rejections in the present writing landscape. Let me elaborate.

This intriguing article floated into my reading space and collided with another one detailing the main reason for manuscript rejections in the present writing landscape. Let me elaborate.

Even seasoned writers get rejections and, with more writers pitching these days, there is an increase in an agent’s slush pile. Given that fewer agents are at their game (blame covid, war, inflation and anything else you like), there is less space for your manuscript to get accepted. If it does, it it pitched to fewer publishers. Therefore, the chance of success is heavily diminished and you could well brace yourself for over 100 rejection letters. Back to the headline:

1. Rejections are not failures

Yes, getting rejections sucks. I’m not here to tell you to suck it up. Getting any sort of literary rejection letter hurts. I know. I’ve been there, literally hundreds of times. (It does get easier. Mostly.)

But here’s the thing: getting rejected means you put your writing out there.

It means you tried.

It means you’ve kept trying.

And it means you’re getting better at writing because you’re spending enough time with it that you’re finishing projects. You are in a position for feedback and critique.

Putting your writing out there tacks guts,

Getting rejected is a sign of bravery and resilience.

It is not a sign of failure, it is a sign of accomplishment.

2. Odds are you’ll get more acceptances

There’s one simple reason to collect rejections like they’re going out of style:

Trying for that many rejections means there are bound to be some acceptances in there, too.

It’s really that simple. Odds are, if you aim for a hundred rejections, you’ll end up with way more acceptances than you would’ve otherwise.

The first year I tried for a hundred rejections, I didn’t make my goal. Why? I ended up with over twenty acceptances. Compared to previous years, I’d quadrupled my acceptance rate. Quadrupled!

I would have never, never hit that many acceptances if I hadn’t had my rejection goal. My goal of rejections made me set aside time each week to look for publications and submit to them. Every single week. It made me commit to prioritizing my writing, and then inevitably increased the odds for some acceptance letters along with the rejections.

I have no control over what an editor likes. I do have control over how many editors see my stories.

And odds are, the more eyes on my work, the more stories I’ll have published.

3. Rejections are motivation

Don’t get mad; get writing.

Stephen King talks about keeping his rejection slips in his book on the writing craft, On Writing. He had a nail in his room and every time he got a rejection letter, he skewered it on the nail. The rejections piling up were a constant motivation to keep writing and to keep submitting.

While collecting literary rejection letters/emails doesn’t sound like a beloved keepsake, that stack of letters will be the day you’re accepted.

The only way to get an acceptance letter is to keep writing—and submitting your work. When rejection is used as motivation instead of discouragement, you start to grow as a writer instead of leaning towards giving up on your dreams of getting published.

Become the former. Set yourself a goal of one hundred literary rejection letters in 2021.

4. Rejections improve your writing

Yep, there is improvement to be had here. Any feedback from an agent or editor is a huge win, since it means they see potential in your story, even if it’s not quite in a place where they’re ready to accept it.

By sending you a personal note, editors and agents not only took the time to help you out, but they also gave you a hint as to how you can be published with them later.

However, more often than not, you will get a form rejection letter. And that’s fine!

Editors and agents receive a ton of slush. They just don’t have enough time to answer everyone, so do your best not to take a literary rejection letter personally. Instead, in this instance, take a look at the types of stories that are getting attention from editors or accepted. What do they have in common?

What do the stories that keep getting rejected over and over again have in common? Studying the difference and tweaking your work so it’s in the acceptance group is a healthy part of the revision process.

That’s how you improve your writing.

5. Having a rejection goal helps your mindset

When you have a goal, you expect to achieve that goal, right? Otherwise setting it is kind of stupid.

Having a goal of one hundred literary rejection letters helps you take the icky blow for each individual rejection easier.

I’ll let you in on a secret. I’d known rejection was part of the writing game when I started writing. I was prepared when I got my first one. I did not cry or react negatively in any way. I’d expected it, after all. (Though I do still remember the publication and the name of the editor.)

I cried when I got my third rejection. There are still some rejections that I take hard. Mostly when it’s a prestigious publication or I’ve made the shortlist only to be ultimately turned down.

But since I have my rejection goal, ninety-nine percent of the time I simply mark it down and send the story out again. Since my actual goal isn’t X number of publications or awards, the rejections don’t seem as important.

And as for the particular publication I mentioned above, the publication and editor only opens for submissions once a year. I submit, and am rejected, every year. I will get published with them someday, though. See my previous points about how more rejection letters equals acceptance letters, as well as using literary rejection letters for motivation. Take the negative word of “rejection” and turn it on its head. Make it something positive!

Let’s do this together.

One hundred rejections, here we come! [article source]

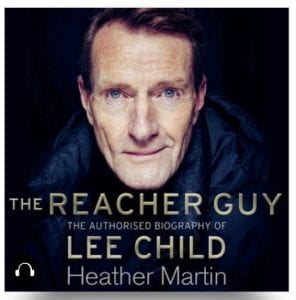

Author Lee Child has published 25 thrillers, featuring Jack Reacher, which have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide.So when he says The Day Of The Jackal is “a year-zero, game-changing thriller, one of the most significant of all time” you listen.

Author Lee Child has published 25 thrillers, featuring Jack Reacher, which have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide.So when he says The Day Of The Jackal is “a year-zero, game-changing thriller, one of the most significant of all time” you listen. set in 1963, about an Englishman hired to assassinate the French president at the time, Charles de Gaulle. But publishers were not interested. After all de Gaulle was very much alive, the mission had obviously failed, so where was the suspense? That, says Child, is the key to its success.

set in 1963, about an Englishman hired to assassinate the French president at the time, Charles de Gaulle. But publishers were not interested. After all de Gaulle was very much alive, the mission had obviously failed, so where was the suspense? That, says Child, is the key to its success.

This intriguing article floated into my reading space and collided with another one detailing the main reason for manuscript rejections in the present writing landscape. Let me elaborate.

This intriguing article floated into my reading space and collided with another one detailing the main reason for manuscript rejections in the present writing landscape. Let me elaborate. On July 20, 1969,

On July 20, 1969,  However, whatever circumstances I find myself in, I have my writing antennae ready to pick up a comment or gesture; a news item or statement, or any snippet that will be useful in my book. For example, my wife and I were on a train in the south of France. I looked over the isle and saw someone who fitted a character I was writing about. Their hair, their shoes, and their facial expression quickly joined the description I needed.

However, whatever circumstances I find myself in, I have my writing antennae ready to pick up a comment or gesture; a news item or statement, or any snippet that will be useful in my book. For example, my wife and I were on a train in the south of France. I looked over the isle and saw someone who fitted a character I was writing about. Their hair, their shoes, and their facial expression quickly joined the description I needed. “There are two sides to every story”

“There are two sides to every story” Maggie Shipstead (left) writes, “John Gardner famously wrote that fiction should be a “vivid, continuous dream,” but some readers’ willingness to dream is more robust than others. Some people will shut a book forever at the first sign of an error, their trust in the writer and their suspension of disbelief irrevocably lost. Others will happily read along through almost anything, swallowing the most preposterous plot points, the most egregious anachronisms, and the most glaring inconsistencies…But I think sloppiness is worth trying to avoid, both out of pure principle (why get something wrong when you could get it right?) and because mistakes can be indicative of an author not pressing hard enough on the world she’s building, not making it sturdy enough, settling for a facade.” In her

Maggie Shipstead (left) writes, “John Gardner famously wrote that fiction should be a “vivid, continuous dream,” but some readers’ willingness to dream is more robust than others. Some people will shut a book forever at the first sign of an error, their trust in the writer and their suspension of disbelief irrevocably lost. Others will happily read along through almost anything, swallowing the most preposterous plot points, the most egregious anachronisms, and the most glaring inconsistencies…But I think sloppiness is worth trying to avoid, both out of pure principle (why get something wrong when you could get it right?) and because mistakes can be indicative of an author not pressing hard enough on the world she’s building, not making it sturdy enough, settling for a facade.” In her “I have a charming relative who is an angry young littérateur of renown. He is maddened by the fact that more people read my books than his. Not long ago we had semi-friendly words on the subject and I tried to cool his boiling ego by saying that his artistic purpose was far, far higher than mine. He was engaged in “The Shakespeare Stakes.” The target of his books was the head and, to some extent at least, the heart. The target of my books, I said, lay somewhere between the solar plexus and, well, the upper thigh. These self-deprecatory remarks did nothing to mollify him and finally, with some impatience and perhaps with something of an ironical glint in my eye, I asked him how he described himself on his passport. “I bet you call yourself an Author,” I said. He agreed, with a shade of reluctance, perhaps because he scented sarcasm on the way. “Just so,” I said. “Well, I describe myself as a Writer. There are authors and artists, and then again there are writers and painters.”

“I have a charming relative who is an angry young littérateur of renown. He is maddened by the fact that more people read my books than his. Not long ago we had semi-friendly words on the subject and I tried to cool his boiling ego by saying that his artistic purpose was far, far higher than mine. He was engaged in “The Shakespeare Stakes.” The target of his books was the head and, to some extent at least, the heart. The target of my books, I said, lay somewhere between the solar plexus and, well, the upper thigh. These self-deprecatory remarks did nothing to mollify him and finally, with some impatience and perhaps with something of an ironical glint in my eye, I asked him how he described himself on his passport. “I bet you call yourself an Author,” I said. He agreed, with a shade of reluctance, perhaps because he scented sarcasm on the way. “Just so,” I said. “Well, I describe myself as a Writer. There are authors and artists, and then again there are writers and painters.”