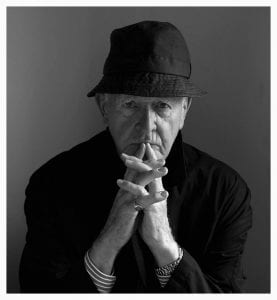

Great writers are capable of breaking common literary conventions. For example, John le Carré delights to tell a story, rather than show it, and this is contrary to good literary advice (a search of ‘show, don’t tell’ yields over 400,000 results on youtube). ‘Telling’ works for le Carré because he is so good at it and because he uses omniscient characters to lay enough information to pull the reader into the plot (emphasis is mine).

Great writers are capable of breaking common literary conventions. For example, John le Carré delights to tell a story, rather than show it, and this is contrary to good literary advice (a search of ‘show, don’t tell’ yields over 400,000 results on youtube). ‘Telling’ works for le Carré because he is so good at it and because he uses omniscient characters to lay enough information to pull the reader into the plot (emphasis is mine).

“Both The Honourable Schoolboy and A Delicate Truth deploy omniscient narrators. Interestingly, omniscience is virtually Le Carré’s default form of narrative method…Without doubt, the subliminal effect of hearing the authorial voice in a Le Carré novel is perhaps the most signal feature of his style. For example, this is how A Delicate Truth begins:

On the second floor of a characterless hotel in the British crown Colony of Gibraltar, a lithe, agile man in his late fifties restlessly paced his bedroom…Certainly it would not have occurred to many people, even in their most fanciful dreams, that he was a middle-ranking British civil servant… dispatched on a top-secret mission of acute sensitivity.”

Here, the omniscient narrator informs the reader of the key fact on page one: the “top-secret mission of acute sensitivity”. It is a confident, almost brazen, rupturing of the modern literary injunction to “show, not tell”. John le Carré is telling us this story, not showing it, and he has all the information.” [source: The New Statesman]

The famous thriller writer, John le Carre wrote, “I think bankers will always get away with whatever they can get away with.” In my new novel, the theme of corrupt (oops, perhaps devious) banks and bankers is one that propels the plot along. It gives motive as well as substance for the unfolding events that cause a group of cunning heisters to plan on diverting huge sums of money away from the banks.

The famous thriller writer, John le Carre wrote, “I think bankers will always get away with whatever they can get away with.” In my new novel, the theme of corrupt (oops, perhaps devious) banks and bankers is one that propels the plot along. It gives motive as well as substance for the unfolding events that cause a group of cunning heisters to plan on diverting huge sums of money away from the banks.