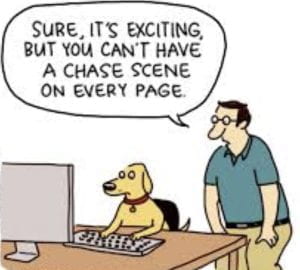

A technique enjoyed by thriller writers is to end each chapter with tension—the kind that makes readers want to turn the page. Along with short chapters, this maintains drama. I get that as a writer, but I also enjoy sudden events. Life is a mix of calm, solitude, relationships, drama, and sudden events or surprises. I would like to think that this reflects in my writing. Here’s some examples of chapter endings from my new book as examples of the different levels of tension. The context is onboard a submarine, under the Arctic.

A technique enjoyed by thriller writers is to end each chapter with tension—the kind that makes readers want to turn the page. Along with short chapters, this maintains drama. I get that as a writer, but I also enjoy sudden events. Life is a mix of calm, solitude, relationships, drama, and sudden events or surprises. I would like to think that this reflects in my writing. Here’s some examples of chapter endings from my new book as examples of the different levels of tension. The context is onboard a submarine, under the Arctic.

Jerry replied in a hushed tone. “If you enter this dark, cold world without a proper ceremony, the King of Ice will pour his wrath on you all. Get to your quarters and into your swimsuits. Be back here by 1700 hours. That gives you twenty minutes. Now go.”

and

Everyone nearby watched, fascinated as Kim’s steady hand scanned back and forth on the large amplifier dial, calibrating the ambient noise, temperature, and depth. She cross-checked the kinematic parameters—speed, direction, and even the supersonic sound waves. The computer was busy, looking for a match in Hammerhead’s extensive database.

Kim was honing in on the rogue visitor. Just a few more adjustments and a result jumped onto her screen.

“Got ya,” she bounced in delight, ripping off her headphones.

and

“Three-five-zero feet and closing.”

“Damn.”

Sailors perspired and clenched their fists. Movements around the Control Room slowed.

Bus Driver whispered the numbers, “Three-three-zero feet, three-zero-zero feet, two-seven-five—hell, we’re going to collide.”

Hawkeye froze, waiting for the sound of metal on metal or, worse, the sound of water flooding the room.

Well, dear bloggers, this may shock you—I am on a long vacation but have no intention to write another book. That’s right, it’s about celebration—celebrating my wife’s very special birthday in Paris. So, writing will take a back seat, though that’s not to say that I won’t find inspiration in being in different places and watching out for interesting characters or settings for my next novel. Will it be a thriller set in Vienna, or a romantic novel based in France? Who knows? The most wonderful thing about writing is that it has few bounds, and the richer the experience (either good or bad) can result in a more satisfying read. Well, that’s the intention.

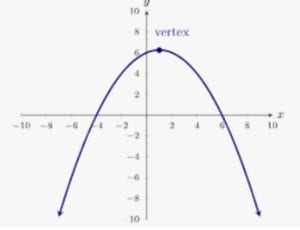

Well, dear bloggers, this may shock you—I am on a long vacation but have no intention to write another book. That’s right, it’s about celebration—celebrating my wife’s very special birthday in Paris. So, writing will take a back seat, though that’s not to say that I won’t find inspiration in being in different places and watching out for interesting characters or settings for my next novel. Will it be a thriller set in Vienna, or a romantic novel based in France? Who knows? The most wonderful thing about writing is that it has few bounds, and the richer the experience (either good or bad) can result in a more satisfying read. Well, that’s the intention. The more I write, the more I find myself believing in the inverse parabola. What do I mean? It’s like this—writing a novel keeps adding words and as the words increase the number of chapters grow too. words–>chapters–>book. At the peak of the writing output (the vertex if you like) the book is finished. But when the editing takes place, the number of words decrease again, like a descending parabola. From my own experience, this editing reduces the word count and often the number of chapters too. This reduction is sometimes painful, cutting out unnecessary dialogue/action/description. What is left is tighter writing, more immediacy and greater tension. Show me a writer who is increasing their word count and I can guess they are still working on an unfinished draft; show me a writer who is reducing their word count, and I know they are heading for a finished finished draft, ready for their literary agent and/or publisher.

The more I write, the more I find myself believing in the inverse parabola. What do I mean? It’s like this—writing a novel keeps adding words and as the words increase the number of chapters grow too. words–>chapters–>book. At the peak of the writing output (the vertex if you like) the book is finished. But when the editing takes place, the number of words decrease again, like a descending parabola. From my own experience, this editing reduces the word count and often the number of chapters too. This reduction is sometimes painful, cutting out unnecessary dialogue/action/description. What is left is tighter writing, more immediacy and greater tension. Show me a writer who is increasing their word count and I can guess they are still working on an unfinished draft; show me a writer who is reducing their word count, and I know they are heading for a finished finished draft, ready for their literary agent and/or publisher. As I turn back to my new novel I have been struggling to link Chapter Two with Chapter Three. The third chapter is a completely different setting (underwater in a submarine) with new characters. How could I link these to help the book flow for my readers?

As I turn back to my new novel I have been struggling to link Chapter Two with Chapter Three. The third chapter is a completely different setting (underwater in a submarine) with new characters. How could I link these to help the book flow for my readers?

When writing, the plot and characters are uppermost in my mind. It’s a subconscious thing and I find myself thinking about events in my novel while drifting off to sleep, only to have them punctuated by fresh thoughts. These make me force myself awake and make the necessary changes while they are fresh – “I’ll forget them in the morning,” I tell myself. There a catch though. In the morning, have to check that the new thought fits the storyline and doesn’t detract from it or overwhelm it; it has to enhance it to be effective. Ah the joys of ruminating – just going over and over my novel, like cows chewing grass:

When writing, the plot and characters are uppermost in my mind. It’s a subconscious thing and I find myself thinking about events in my novel while drifting off to sleep, only to have them punctuated by fresh thoughts. These make me force myself awake and make the necessary changes while they are fresh – “I’ll forget them in the morning,” I tell myself. There a catch though. In the morning, have to check that the new thought fits the storyline and doesn’t detract from it or overwhelm it; it has to enhance it to be effective. Ah the joys of ruminating – just going over and over my novel, like cows chewing grass: A technique enjoyed by thriller writers is to end each chapter with tension—the kind that makes readers want to turn the page. Along with short chapters, this maintains drama. I get that as a writer, but I also enjoy sudden events. Life is a mix of calm, solitude, relationships, drama, and sudden events or surprises. I would like to think that this reflects in my writing. Here’s some examples of chapter endings from my new book as examples of the different levels of tension. The context is onboard a submarine, under the Arctic.

A technique enjoyed by thriller writers is to end each chapter with tension—the kind that makes readers want to turn the page. Along with short chapters, this maintains drama. I get that as a writer, but I also enjoy sudden events. Life is a mix of calm, solitude, relationships, drama, and sudden events or surprises. I would like to think that this reflects in my writing. Here’s some examples of chapter endings from my new book as examples of the different levels of tension. The context is onboard a submarine, under the Arctic. Let’s refocus the statement. Who is your champion—who spurs you on and keeps you focused? Why gives you encouragement in your writing, and feedback to improve? Where do you turn when you have received a reject and who do you rejoice with when you get asked for a full? That’s right, you need to be connected to a group, or someone who cares.

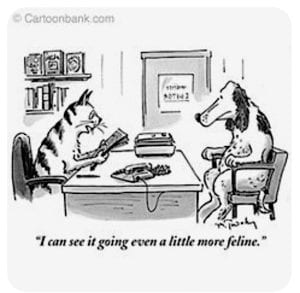

Let’s refocus the statement. Who is your champion—who spurs you on and keeps you focused? Why gives you encouragement in your writing, and feedback to improve? Where do you turn when you have received a reject and who do you rejoice with when you get asked for a full? That’s right, you need to be connected to a group, or someone who cares. What value do I place on a professional editor? HEAPS!

What value do I place on a professional editor? HEAPS!