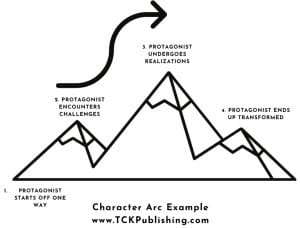

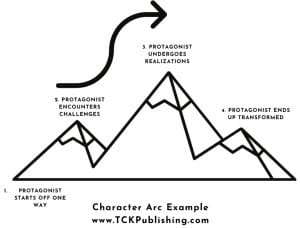

Oh how we love character arcs (youtube is full of them). A good protagonist ends up bad, or a bad one turns good. Or, a level-headed character stays that way to meet challenges head-on. News channels love to publish about someone who has ‘fallen from grace’ or done something awful. We all have stories about fallen characters. I am reminded of what the great Apostle Paul said (in Romans 3:23) – “all have sinned, and come short…” In other words, none of us are perfect. We aim to be better (or worse) and our character trends or arcs upwards or downwards, or stays level. An arc is a line that is part of a circle; character arcs are the same and three types are listed below. However, there is another arc you should consider, and it is the arc of electricity makes as it moves from one source to another. A spark arcs as an electrical discharge between two electrodes. We saw that in a spectacular way a few days ago. Our stove caught fire and, when we looked inside, there were sparks arcing at the back of the main oven. In writing, I like to think of this arcing as being between characters. Sparks fly as conflict develops and, as conflict develops, you want to keep reading. Now, back to character arcs:

Here are three basic character arcs (source from tkpublishing):

What is a Positive Character Arc?

A positive change arc is one in which the protagonist undergoes a positive transformation. This usually includes a neat resolution at the end, where, because of their internal change, the character finally achieves their goals. An example of a positive character arc in classic literature is that of Marilla, the woman who adopts Anne in Anne of Green Gables. Marilla starts off uninterested in keeping the little girl, but as the story progresses, we see her developing a subtle but strong affection for Anne.

Negative Character Arcs

But not all stories have a happy ending: a negative change arc is one that still shows how your character develops, but not toward a positive transformation. Instead, this arc illustrates a downward spiral. However, the basic “arc” pattern remains the same, as it is still about how your protagonist starts one way and ends up another. Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is a classic example of a negative character arc. From the beginnings of her adultery, Anna Karenina continues to spiral downward, only to reach a tragic end at the end of the book.

What Is a Flat Character Arc?

Another character arc is the flat arc, wherein the character already has their beliefs in place and uses them to solve problems throughout the story; but even as the story ends, the character remains mostly the same. The development of Miss Maudie, the children’s aunt in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, is an example of a flat character arc. She remains steadfast in her beliefs from her first scene until the end of the book.

[PS: my main character is an ageing spy who has second-thoughts about the value of his career. I will say no more.]

There is much debate and mystery to the idea of having to turn wine bottles to improve their flavour and consistency.

There is much debate and mystery to the idea of having to turn wine bottles to improve their flavour and consistency.

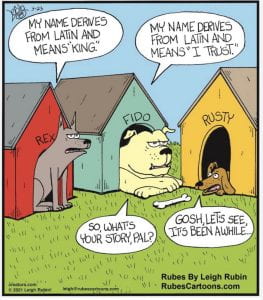

William Shakespeare uses this line in his play Romeo and Juliet to convey the idea that the naming of things is irrelevant. Now, who would I be to question Shakespeare. But, a name may be relevant in conveying something more important than the person or object? For example, we name our children after their grandparents for example. In my new novel, why did I chose the name Captain Ted Cooper for my submarine commander? Ted Cooper was a close neighbour and friend I knew in high school. We were both in a school play – King Lear as it happens. I remember being a guard in the play and Ted was backstage. After the last performance, to celebrate we sailed a twenty-four foot wooden boat into the night. We were blind like King Lear – unable to see in the dark – and eventually beached on an island to get some sleep. The boat leaked, but we happily explored and had a great time. Ted went on to serve in the merchant navy as a captain before passing away at a rather young age. Using his name seemed most appropriate for the submarine commander in my book. Any other name was (sorry, Shakespeare) not quite as sweet. Of course, I did check out the list of USA sub commanders, the most famous being

William Shakespeare uses this line in his play Romeo and Juliet to convey the idea that the naming of things is irrelevant. Now, who would I be to question Shakespeare. But, a name may be relevant in conveying something more important than the person or object? For example, we name our children after their grandparents for example. In my new novel, why did I chose the name Captain Ted Cooper for my submarine commander? Ted Cooper was a close neighbour and friend I knew in high school. We were both in a school play – King Lear as it happens. I remember being a guard in the play and Ted was backstage. After the last performance, to celebrate we sailed a twenty-four foot wooden boat into the night. We were blind like King Lear – unable to see in the dark – and eventually beached on an island to get some sleep. The boat leaked, but we happily explored and had a great time. Ted went on to serve in the merchant navy as a captain before passing away at a rather young age. Using his name seemed most appropriate for the submarine commander in my book. Any other name was (sorry, Shakespeare) not quite as sweet. Of course, I did check out the list of USA sub commanders, the most famous being  The water in a flowing river ripples over rocks and this keeps it fresh. I hope my stories work like that—like a flowing stream that has a few eddies and a few quiet ponds, but then races downhill over rapids to arrive full of oxygen and life. Ask yourself this question as a writer; does my writing suck oxygen from the reader or pump oxygen into them? I have had the privilege of taking high school students down New Zealand’s Whanganui River. By the end of the trip they were all looking forward to more rapids and became exited when they could hear the roar of water ahead of them. Stories can be like that too.

The water in a flowing river ripples over rocks and this keeps it fresh. I hope my stories work like that—like a flowing stream that has a few eddies and a few quiet ponds, but then races downhill over rapids to arrive full of oxygen and life. Ask yourself this question as a writer; does my writing suck oxygen from the reader or pump oxygen into them? I have had the privilege of taking high school students down New Zealand’s Whanganui River. By the end of the trip they were all looking forward to more rapids and became exited when they could hear the roar of water ahead of them. Stories can be like that too.

Waiting is a difficult game and not many of us are built to handle it well. “Waiting for what?” you might ask. It could be waiting for your next plot idea, next book concept, or waiting for a literary agent to get back to you after a full manuscript request. So, to ease the pain, here are a few suggestions:

Waiting is a difficult game and not many of us are built to handle it well. “Waiting for what?” you might ask. It could be waiting for your next plot idea, next book concept, or waiting for a literary agent to get back to you after a full manuscript request. So, to ease the pain, here are a few suggestions:

However, whatever circumstances I find myself in, I have my writing antennae ready to pick up a comment or gesture; a news item or statement, or any snippet that will be useful in my book. For example, my wife and I were on a train in the south of France. I looked over the isle and saw someone who fitted a character I was writing about. Their hair, their shoes, and their facial expression quickly joined the description I needed.

However, whatever circumstances I find myself in, I have my writing antennae ready to pick up a comment or gesture; a news item or statement, or any snippet that will be useful in my book. For example, my wife and I were on a train in the south of France. I looked over the isle and saw someone who fitted a character I was writing about. Their hair, their shoes, and their facial expression quickly joined the description I needed. Here’s the best advice that helps my writing: I need to review it regularly: “Be myself and be authentic. Don’t try to put on a voice that isn’t my own. Keep my characters genuine and real. Readers will pick up if I’m lying, and they will put my book down. Keep my writing simple and keep it honest.”

Here’s the best advice that helps my writing: I need to review it regularly: “Be myself and be authentic. Don’t try to put on a voice that isn’t my own. Keep my characters genuine and real. Readers will pick up if I’m lying, and they will put my book down. Keep my writing simple and keep it honest.” Motive is the glue that holds a thriller together, and keeps the plot racing to its conclusion.

Motive is the glue that holds a thriller together, and keeps the plot racing to its conclusion.