The process to add an eBook in Kindle format (epub) was quite simple. The formatting was done by Rakib (from Fiverr.com) and the only modification I needed to add was the book description from the rear cover – since only the front cover is shown on Kindle. Uploading took about ten minutes. The book cover design was from Lamar H (also from fiverr) and his work is quick, with just a few days needed to make a few tweaks to the design. The most difficult part of the self-publishing process is getting a fully edited manuscript ready. With my first book, this took a few months; with MUTINY it was about five years! Click here to order MUTINY.

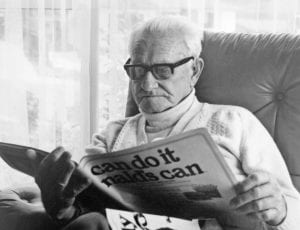

Hooray, he final edits are now complete and, if I am allowed to say so, I enjoyed reading my draft again, especially the moments of humor. The end-twist was a nice surprise and I hope you agree. Who doesn’t love a good novel – one that comes from the challenges of life? My first novel – 3 WISE MEN – was less polished than I would have liked but, at least with self-publishing, I had the chance to reprint and improve it. My father (pictured here) was an avid writer and taught creative writing. I can still hear the tap, tap,tap of his golf-ball typewriter as he plowed into another short story (with no Word docs in those days). He survived WWII and had lots of stories. I am sure his writing became cathartic for him. His library was full of interesting books and these gave me plenty to devour in my spare time. Now, back to finding my cover designer!

Hooray, he final edits are now complete and, if I am allowed to say so, I enjoyed reading my draft again, especially the moments of humor. The end-twist was a nice surprise and I hope you agree. Who doesn’t love a good novel – one that comes from the challenges of life? My first novel – 3 WISE MEN – was less polished than I would have liked but, at least with self-publishing, I had the chance to reprint and improve it. My father (pictured here) was an avid writer and taught creative writing. I can still hear the tap, tap,tap of his golf-ball typewriter as he plowed into another short story (with no Word docs in those days). He survived WWII and had lots of stories. I am sure his writing became cathartic for him. His library was full of interesting books and these gave me plenty to devour in my spare time. Now, back to finding my cover designer!