“There’s a statistic that circulates the publishing world that only one in six thousand writers will sign with a literary agent. And only a very small percentage of those will ever get published. So what’s the point in trying?”

Such a relevant question. Why climb Everest? Why row across an ocean? Why be a school principal? Why renovate another house? Why? Why? Why?

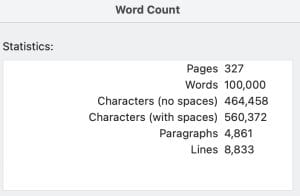

I’m going to struggle with a sensible answer, but here goes. I keep trying because I want to reach the greatest audience and I keep trying because I want my heist-thriller to be as polished as possible, which will not happen if I self-publish. Oh, there are many other illogical reasons too :-). Have I felt like giving up? Yes, and even more in recent days. Having a request for my full manuscript created hope to land a literary agent, but this was followed four weeks later by a “No.” After this glimmer of hope it was back to a full re-edit, and chapter reorganisation, before sending out a few more submissions. The recent rise of Artificial Intelligence, and a huge global interest in deep-sea submersibles (with the Titan implosion) should help propel my novel. I’m just waiting for a literary agent to agree.

I’m going to struggle with a sensible answer, but here goes. I keep trying because I want to reach the greatest audience and I keep trying because I want my heist-thriller to be as polished as possible, which will not happen if I self-publish. Oh, there are many other illogical reasons too :-). Have I felt like giving up? Yes, and even more in recent days. Having a request for my full manuscript created hope to land a literary agent, but this was followed four weeks later by a “No.” After this glimmer of hope it was back to a full re-edit, and chapter reorganisation, before sending out a few more submissions. The recent rise of Artificial Intelligence, and a huge global interest in deep-sea submersibles (with the Titan implosion) should help propel my novel. I’m just waiting for a literary agent to agree.

But, the greatest reason is ‘persistence‘ – never giving up on a higher goal and I hope I am able to reach it soon.

When writing, the plot and characters are uppermost in my mind. It’s a subconscious thing and I find myself thinking about events in my novel while drifting off to sleep, only to have them punctuated by fresh thoughts. These make me force myself awake and make the necessary changes while they are fresh – “I’ll forget them in the morning,” I tell myself. There a catch though. In the morning, have to check that the new thought fits the storyline and doesn’t detract from it or overwhelm it; it has to enhance it to be effective. Ah the joys of ruminating – just going over and over my novel, like cows chewing grass:

When writing, the plot and characters are uppermost in my mind. It’s a subconscious thing and I find myself thinking about events in my novel while drifting off to sleep, only to have them punctuated by fresh thoughts. These make me force myself awake and make the necessary changes while they are fresh – “I’ll forget them in the morning,” I tell myself. There a catch though. In the morning, have to check that the new thought fits the storyline and doesn’t detract from it or overwhelm it; it has to enhance it to be effective. Ah the joys of ruminating – just going over and over my novel, like cows chewing grass:

The Great Gatsby is now recognised as a masterpiece. But, F. Scott Fitzgerald (left) never saw his book become a success. In fact, at his untimely death at the age of 44, he had earned a grand total of $13.13 in royalties. When it was published in 1925, Gatsby sold a disappointing 21,000 copies. And there were reportedly still copies from the second printing in the Scribner warehouse when Fitzgerald died in 1940. It’s shocking how long it took The Great Gatsby to be considered a classic. It wasn’t until April 24, 1960, for example, that The New York Times wrote: “It is probably safe now to say that The Great Gatsby is a classic of twentieth-century American fiction.”

The Great Gatsby is now recognised as a masterpiece. But, F. Scott Fitzgerald (left) never saw his book become a success. In fact, at his untimely death at the age of 44, he had earned a grand total of $13.13 in royalties. When it was published in 1925, Gatsby sold a disappointing 21,000 copies. And there were reportedly still copies from the second printing in the Scribner warehouse when Fitzgerald died in 1940. It’s shocking how long it took The Great Gatsby to be considered a classic. It wasn’t until April 24, 1960, for example, that The New York Times wrote: “It is probably safe now to say that The Great Gatsby is a classic of twentieth-century American fiction.” It’s a catchy title – “Flop Masterpiece” – and enough to make you want to see it. “An ambitious, budget-busting adventure-thriller set in a South American oil refinery town and its surrounding mountainous jungle, Sorcerer was intended as a loose remake of Henri-Georges Cluozot’s undisputed 1951 classic Wages of Fear. It was also well-poised to be a gargantuan flop when it was released the same summer weekend as George Lucas’ much more straightforward blockbuster Star Wars.” [source: BBC]. So, until Star Wars came along and took the limelight, Sorcerer was a masterpiece? I love the oxymoron, but I guess that, at the end of a long day, I am NOT inclined to want to see a “flop masterpiece.”

It’s a catchy title – “Flop Masterpiece” – and enough to make you want to see it. “An ambitious, budget-busting adventure-thriller set in a South American oil refinery town and its surrounding mountainous jungle, Sorcerer was intended as a loose remake of Henri-Georges Cluozot’s undisputed 1951 classic Wages of Fear. It was also well-poised to be a gargantuan flop when it was released the same summer weekend as George Lucas’ much more straightforward blockbuster Star Wars.” [source: BBC]. So, until Star Wars came along and took the limelight, Sorcerer was a masterpiece? I love the oxymoron, but I guess that, at the end of a long day, I am NOT inclined to want to see a “flop masterpiece.”