What makes a good read? Surprises and lots of them. OK, what do I mean by “surprises?” Surprises are out-of-the-blue moments that interrupt the flow of the novel and take it, or a character, in a different direction. Too many surprises and they are not surprises anymore. That’s why I only use a few, and only as necessary to enhance the plot. In my novel, the end chapters reference the kind of surprises that we enjoyed as children at Christmas time. Something like this;

What makes a good read? Surprises and lots of them. OK, what do I mean by “surprises?” Surprises are out-of-the-blue moments that interrupt the flow of the novel and take it, or a character, in a different direction. Too many surprises and they are not surprises anymore. That’s why I only use a few, and only as necessary to enhance the plot. In my novel, the end chapters reference the kind of surprises that we enjoyed as children at Christmas time. Something like this;

[“Thank you,” says Rian. “I have another surprise for you too.”

“Oh?”

“Please close your eyes.”

My senses peak. I hear the slap, slap of halyards against the yacht mast and I’m reminded of the tap, tap of Sweetman’s cane at The Rock Hotel, though that was a lifetime ago.

Seagulls squawk. I’m getting hot and the anticipation is killing me. Then, high heels come clacking across the sandstone terrace, getting louder. A shadow darkens my eyes and a tender arm wraps around my neck. The kiss is sweet and soft and the air wafts with perfume; a sexy mix of jasmine and vanilla. My mind is alive with intrigue.

“Who?” I ask.

“It’s been a while,” she replies. The voice is lilting and familiar, yet I can’t place it. I dive inside my memory banks, but they are empty except for the hint of a French accent. Was she in Paris? Damn, I used to recall names with ease and am about to ask for a clue when she says, “You can open your eyes now.”

I look up. Golden hair cascades in the sun and her face is shadowed under an old straw hat, its tattered red ribbon fluttering in the breeze. My eyes adjust and my mind catches up.

“Claudine, what a surprise and, I must say, a pleasure too.”

“My name is now Chloé Dupont,” she laughs.

“It’s been a long time. You’ve changed,” I add.

She smiles and wags a finger asking, “How have I changed?”

“You look more beautiful than ever, and happier too.” She giggles and kisses me again.

“Another glass please, Rian,” I say. “Let’s celebrate Watershed with our new guest, the lovely Chloé Dupont.” The day seems brighter. She rests her glass, tosses her hair and hands me a parcel.

“A small gift for you,” she chuckles.

“You shouldn’t have,” I protest.

Her reply puts me in my place when she says, “It’s better to give than receive.” I like that and must remember it.

The Christmas wrapping is enticing and topped with a large, yellow bow.

“I wonder what this could be?” I reply, shaking it in the way I did as an excited young boy on Christmas Eve. I loved to see the present wrapped and stacked beneath the family tree, and try to guess the contents of each one—perhaps a toy rifle for me to fight off the enemy, or a sword to cut off their heads? Better still, the whole outfit—a Lone Ranger suit, complete with mask and pistols? I made several attempts to discover the wrapped secrets. My parents never approved, but Chloé encourages me.

She laughs, “Can you guess what it is?”

“It feels solid,” I say. “A strange shape, rounded at each end.”

“Just a small keepsake,” she adds.]

I guess you want to know what the surprise is? Aha, wait for the book 🙂

The one sentence pitch is the essence or heart of a book, the line that tells people about your book and makes it sound awesome.

The one sentence pitch is the essence or heart of a book, the line that tells people about your book and makes it sound awesome. There’s one thing every writer needs to master, and that is how to leave a lasting impression on readers—how to end their story. Should it be unresolved or ambiguous; unexpected or dramatic? As writers, we have plenty of options. So, you might ask, what worked for me in my latest novel? More on this to come, suffice to say that I changed the ending a few times, more or less in keeping with my editing and having more time to review it. In the end (pun intended), I changed the ending to tie up a loose end near the beginning. I could tell you more, but that would be giving the plot away. OK, here’s a glimpse of the beginning of the final chapter:

There’s one thing every writer needs to master, and that is how to leave a lasting impression on readers—how to end their story. Should it be unresolved or ambiguous; unexpected or dramatic? As writers, we have plenty of options. So, you might ask, what worked for me in my latest novel? More on this to come, suffice to say that I changed the ending a few times, more or less in keeping with my editing and having more time to review it. In the end (pun intended), I changed the ending to tie up a loose end near the beginning. I could tell you more, but that would be giving the plot away. OK, here’s a glimpse of the beginning of the final chapter: Minimize identifying tags

Minimize identifying tags What’s in a name? Everything. A few years ago a Chinese friend of mine rang to ask if New Zealand baby names had meanings. “Of course,” I said. He next asked, “What name means mistake?”

What’s in a name? Everything. A few years ago a Chinese friend of mine rang to ask if New Zealand baby names had meanings. “Of course,” I said. He next asked, “What name means mistake?” Finding the right literary agent is harder than finding a partner. When I co-authored my school textbook, the editor from Macmillan’s was perfect—professional, yet sympathetic; warm and encouraging, though not reluctant to steer us in the right direction. She knew her craft and the final product was excellent. When it comes to novels, I am no expert on literary agents because I have yet to find the right one. But, I am sure that when I do, they will be like my textbook editor and have my best interests at heart. Meanwhile, I keep working on producing the very best manuscript I can; one that is polished, error free, and compelling in terms of plot and pace. I have learned not to treat my agent query like a round of speed-dating, but to focus on the agent who has the same interests as me and the experience to navigate the best publishing deal. How long will this take? Months or years. Does it matter if the novel is able to stand the test of time?

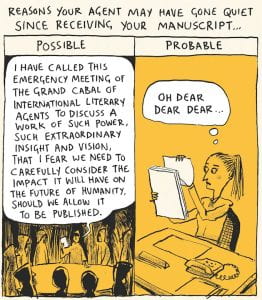

Finding the right literary agent is harder than finding a partner. When I co-authored my school textbook, the editor from Macmillan’s was perfect—professional, yet sympathetic; warm and encouraging, though not reluctant to steer us in the right direction. She knew her craft and the final product was excellent. When it comes to novels, I am no expert on literary agents because I have yet to find the right one. But, I am sure that when I do, they will be like my textbook editor and have my best interests at heart. Meanwhile, I keep working on producing the very best manuscript I can; one that is polished, error free, and compelling in terms of plot and pace. I have learned not to treat my agent query like a round of speed-dating, but to focus on the agent who has the same interests as me and the experience to navigate the best publishing deal. How long will this take? Months or years. Does it matter if the novel is able to stand the test of time? William Golding’s most famous book, Lord of the Flies, had been rejected by every publisher he sent it to – until an editor at Faber pulled his manuscript off the rejection pile.

William Golding’s most famous book, Lord of the Flies, had been rejected by every publisher he sent it to – until an editor at Faber pulled his manuscript off the rejection pile. The analogy is cutting and polishing diamonds. Cutting is crucial, and the same applies to a manuscript. In my latest script, the rough draft had an opening chapter that I cut in order to begin at a more important part of the plot. For a diamond, the final polishing of all the facets is a crucial step in determining the quality and beauty of the finished gem. This takes far more time and painstaking attention to detail. I would have to say that this process of polishing the script, editing and re-editing is taking far longer than I expected. But, I guess I am my worst critic and I am at the level of getting ruthless with each word now. Hopefully, the final product will be polished enough to pass the critic test.

The analogy is cutting and polishing diamonds. Cutting is crucial, and the same applies to a manuscript. In my latest script, the rough draft had an opening chapter that I cut in order to begin at a more important part of the plot. For a diamond, the final polishing of all the facets is a crucial step in determining the quality and beauty of the finished gem. This takes far more time and painstaking attention to detail. I would have to say that this process of polishing the script, editing and re-editing is taking far longer than I expected. But, I guess I am my worst critic and I am at the level of getting ruthless with each word now. Hopefully, the final product will be polished enough to pass the critic test.