This may, or may not, help budding writers: What is the best way to edit your manuscript? Here’s my take, based on the experience of two novels:

Step 1: Finish your Manuscript, then throw it aside for a few weeks. Return to it and read it through, noting obvious errors. Each time you step away from your manuscript you come back to it from a fresh perspective. Note: your first draft is always (yes, always) inadequate.

Step 2: Use an Online Editor. I like using prowritingaid or, more recently, grammarly. Both of these help identify issues such as repeated phrases, over-use of adverbs, sentence lengths, etc. I don’t recommend paying a subscription service, unless for a short period (e.g. a month) in order to check your entire manuscript. A feature I liked as the one where (in prowritingaid) where you can compare your style to another author. You may not be a Hemingway fan, but I like the simplicity of checking chapters in the Hemingway app. Here’s an example from my new novel (with the Hemingway result alongside);

Nikolai had a glass in hand and a faraway look. The lighting cast deep shadows in the folds of his face. He seemed angry, or drunk, or both.

Nikolai had a glass in hand and a faraway look. The lighting cast deep shadows in the folds of his face. He seemed angry, or drunk, or both.

“Wow, that’s a stunning photo of the old man and the sea; a perfect Hemingway moment.”

“I read a Hemingway book at school.”

“Which one? He wrote many.”

“The one about an old man and the sea.”

“About catching a big fish?”

“You remember. Yes, a poor fisherman in Cuba had caught nothing for eighty-four days.”

“It’s been that long since I had a boyfriend. How do you know this detail from the novel?”

“Because it was the same number of days as the title of another book I read, called Nineteen Eight Four.”

“Oh, I see what you mean. “Did you like the story about the old man and his fishing?”

“I loved it because it was the shortest novel we had in our English course. I had to learn some quotes for the final exam, such as, ‘Why do old men wake so early? Is it to have one longer day?'”

“I bet the old man we just saw woke up early.”

“And now, he’s fortified for a long day.” They giggled.

“How old do you think he was?”

“Seventy? Eighty? It was difficult to tell.”

“No idea. I looked at my phone for a bit and missed his exit.”

“You’re always on your phone. If you weren’t married to it you might find a boyfriend.”

“Did you ever have the hots for Hemingway?”

“Course not, I just loved his writing; short, intense, and so easy to read.”

“But you must have lusted after his type; a rugged outdoor man with a bushy beard and all that?”

“No, silly. Even if I had fallen for him, it would be short-lived.”

“He had four wives. His longest marriage was to his writing, and even that had a sad ending.”

“He wrote the last chapter of his life. Like his relationships, it was brief.”

Step 3: Join a Writing Circle. This is, I’m my humble opinion, the MOST important step. Get a writing-circle to review your work. This circle should consist of other writers or readers in your genre who will give constructive advice and not hold back on any criticism. For example, one of my fellow writers gave such good feedback that I rearranged my chapter order, changed the ending, and built a more authentic and powerful plot. And I was able to reciprocate and also offer him advice on his new book.

Step 4: Find a Professional Editor. There are many people who have experience in the publishing trade who are happy to review your work. I used one to check my submission trio – the Query Letter, Synopsis, and first three chapters. Their fixes and recommendations were so good that I asked them to check over other key chapters in my novel. What I especially liked was an experienced editor’s positive encouragement with, “I have a good feeling about this book.” Now, I just need a literary agent to agree.

Final Note: Don’t let any of the above steps change your own writing style. Stay true to who you are as a writer and use the steps to improve your style, rather than force it into someone else’s.

“I have a charming relative who is an angry young littérateur of renown. He is maddened by the fact that more people read my books than his. Not long ago we had semi-friendly words on the subject and I tried to cool his boiling ego by saying that his artistic purpose was far, far higher than mine. He was engaged in “The Shakespeare Stakes.” The target of his books was the head and, to some extent at least, the heart. The target of my books, I said, lay somewhere between the solar plexus and, well, the upper thigh. These self-deprecatory remarks did nothing to mollify him and finally, with some impatience and perhaps with something of an ironical glint in my eye, I asked him how he described himself on his passport. “I bet you call yourself an Author,” I said. He agreed, with a shade of reluctance, perhaps because he scented sarcasm on the way. “Just so,” I said. “Well, I describe myself as a Writer. There are authors and artists, and then again there are writers and painters.”

“I have a charming relative who is an angry young littérateur of renown. He is maddened by the fact that more people read my books than his. Not long ago we had semi-friendly words on the subject and I tried to cool his boiling ego by saying that his artistic purpose was far, far higher than mine. He was engaged in “The Shakespeare Stakes.” The target of his books was the head and, to some extent at least, the heart. The target of my books, I said, lay somewhere between the solar plexus and, well, the upper thigh. These self-deprecatory remarks did nothing to mollify him and finally, with some impatience and perhaps with something of an ironical glint in my eye, I asked him how he described himself on his passport. “I bet you call yourself an Author,” I said. He agreed, with a shade of reluctance, perhaps because he scented sarcasm on the way. “Just so,” I said. “Well, I describe myself as a Writer. There are authors and artists, and then again there are writers and painters.”

Nikolai had a glass in hand and a faraway look. The lighting cast deep shadows in the folds of his face. He seemed angry, or drunk, or both.

Nikolai had a glass in hand and a faraway look. The lighting cast deep shadows in the folds of his face. He seemed angry, or drunk, or both. Some days the words just flow. Hundreds, maybe thousands of them in a rush. Some days you feel so high. Some days you laugh at your own funny parts, and cry at the sad ones. Some days you know that this book is The One.

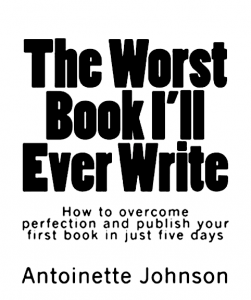

Some days the words just flow. Hundreds, maybe thousands of them in a rush. Some days you feel so high. Some days you laugh at your own funny parts, and cry at the sad ones. Some days you know that this book is The One. Don’t you love this book title? I remember reading somewhere that an author’s first book is ‘always their worst’. I loathed that thought and was determined to disprove it. Yet, the final draft of my first book was so rough that I had to completely re-edit and improve it.

Don’t you love this book title? I remember reading somewhere that an author’s first book is ‘always their worst’. I loathed that thought and was determined to disprove it. Yet, the final draft of my first book was so rough that I had to completely re-edit and improve it. Motive is the glue that holds a thriller together, and keeps the plot racing to its conclusion.

Motive is the glue that holds a thriller together, and keeps the plot racing to its conclusion. I’m playing with words again and, this time, lingering over a short section of my final chapter. Here’s the original:

I’m playing with words again and, this time, lingering over a short section of my final chapter. Here’s the original: I once heard John Irving give a lecture on his process at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, an in-depth account of the way his novels come to be. He kicked it off by writing a single sentence on the chalkboard—the last line of Last Night in Twisted River. All his books begin with the ending, Irving explained, a capstone he works and reworks until it’s ready. From there, he’ll generate a detailed summary that ultimately builds towards the finale. Only when he has the synopsis and last sentence in hand will he actually start writing. I remember being fascinated by this. The approach had clearly been successful, and made sense in theory, and yet was so unlike any creative strategy that had ever worked for me. Which is an important thing to keep in mind when trafficking in the familiar genre of writing advice: Just because John Irving does it that way doesn’t mean you should. Not only is every writer different, but each poem, each story and essay, each novel, has its own formal requirements. Advice might be a comfort in the moment, but the hard truth is that literary wisdom can be hard to systematize. There’s just no doing it the same way twice. And yet. In the five years I’ve spent interviewing authors for The Atlantic’s “By Heart” series, it’s been impossible to ignore the way certain ideas tend to come up again and again. Between the column and the book I’ve engaged a diverse group of more than 150 writers, a large sample size, that nonetheless has some defining traits. Here are the recurring ideas, distilled from dozens of conversations, that I think will most help you—no matter how unorthodox your process, how singular your vision.

I once heard John Irving give a lecture on his process at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, an in-depth account of the way his novels come to be. He kicked it off by writing a single sentence on the chalkboard—the last line of Last Night in Twisted River. All his books begin with the ending, Irving explained, a capstone he works and reworks until it’s ready. From there, he’ll generate a detailed summary that ultimately builds towards the finale. Only when he has the synopsis and last sentence in hand will he actually start writing. I remember being fascinated by this. The approach had clearly been successful, and made sense in theory, and yet was so unlike any creative strategy that had ever worked for me. Which is an important thing to keep in mind when trafficking in the familiar genre of writing advice: Just because John Irving does it that way doesn’t mean you should. Not only is every writer different, but each poem, each story and essay, each novel, has its own formal requirements. Advice might be a comfort in the moment, but the hard truth is that literary wisdom can be hard to systematize. There’s just no doing it the same way twice. And yet. In the five years I’ve spent interviewing authors for The Atlantic’s “By Heart” series, it’s been impossible to ignore the way certain ideas tend to come up again and again. Between the column and the book I’ve engaged a diverse group of more than 150 writers, a large sample size, that nonetheless has some defining traits. Here are the recurring ideas, distilled from dozens of conversations, that I think will most help you—no matter how unorthodox your process, how singular your vision. It can take 21 months or more to cut a diamond into sparkling perfection. Rushing the process could lead to excessive diamond wastage, unnecessary ugly inclusions and poor shaping. The Diamond cutting business is a prime example of an industry in which “Slow and Steady” wins the day. The same applies to editing and polishing a manuscript. I, for one, have been too keen to take my rough manuscript and hoped it would pass the keen eyes of an accomplished literary agent, only to realise too late that the work needed many more months of fine revision. My humble experience has taught me to not rush the process, and take as long as it needs to make it ‘shine.’ With my first book, 3 WISE MEN, I was not happy until about a year after the first version; with my new book, it has taken a similar length of time to get feedback and re-work the ‘final’ draft. I am so pleased that I slowed down the revision process and hope my readers will be too. A good red wine needs to be opened and sit for a while, allowing it to “breathe”and soften the flavours and release enhancing aromas. Writing is no different? No. JD Salinger took 10 years to write Catcher in the Rye, and the first Harry Potter instalment was six years in the making. Time heals many things and writing is no different.

It can take 21 months or more to cut a diamond into sparkling perfection. Rushing the process could lead to excessive diamond wastage, unnecessary ugly inclusions and poor shaping. The Diamond cutting business is a prime example of an industry in which “Slow and Steady” wins the day. The same applies to editing and polishing a manuscript. I, for one, have been too keen to take my rough manuscript and hoped it would pass the keen eyes of an accomplished literary agent, only to realise too late that the work needed many more months of fine revision. My humble experience has taught me to not rush the process, and take as long as it needs to make it ‘shine.’ With my first book, 3 WISE MEN, I was not happy until about a year after the first version; with my new book, it has taken a similar length of time to get feedback and re-work the ‘final’ draft. I am so pleased that I slowed down the revision process and hope my readers will be too. A good red wine needs to be opened and sit for a while, allowing it to “breathe”and soften the flavours and release enhancing aromas. Writing is no different? No. JD Salinger took 10 years to write Catcher in the Rye, and the first Harry Potter instalment was six years in the making. Time heals many things and writing is no different.